Stamp your feet harder.

Your steps are all wrong.

Your feet are not making the right sound.

Correct your lines.

Why do your feet look so heavy?

Work on your lower body. Tuck your bum in. No hip movement.

Touch the floor. Bend, bend more, bend till it hurts.

Enjoy the pain.

Words scraped against my brain as I Iay down, exhausted, in my stark white hostel room. I tried to find comfort in the lingering smell of the oil my roommate was massaging her knees with—that smell spelt care. Setting my alarm for five the next morning, my innards groaned. I looked at the calendar where my roommate struck the days off. And that was when the realisation struck. After 19 years of dancing, I dreaded dance.

I had been reluctant to go to dance classes before. Occasionally, I’ve dragged my feet, made excuses and bunked a few classes. I didn’t have the cultural or economic capital to think of doing a solo show—I just never knew how to. I have rolled my eyes at expectations of being respectful, have been told that I don’t have the face or the height to be a solo/lead dancer, and have been shamed for sweating and smelling (!).

For a long time, I was ashamed to tell my friends at university in Kolkata that I dance. That I’m a ‘classical’ dancer. I was inarticulately aware of the dissonance between the political beliefs I tended to through readings, listening to discussions, being part of them when I could find the words and watching campus politics unfold from a distance—and the acutely supremacist politics of all Indian classical dances.

Bharatanatyam has reached us, throngs of students spread across cities, towns, states and countries, through decades of lies obscuring its history.

A sacred dance as old as the Vedas, a spiritual practice, art that morally uplifts, our unbroken tradition, Hindu culture—it is impossible to save oneself from these randomly and oft-hurled catchphrases in the Bharatanatyam classrooms.

It’s not only history that these words mystify, but the present also gets muddled up and remains inaccessible to those without resources.

I was sure that my dance would only make me more of an outsider in that exclusively ‘progressive’ space where I already was an invisible speck on the wall. Nothing but the thrill of moving time and space in the only way my body knew, the abundance I felt in my body for those moments kept me living this contradiction for many years. That, and a distant hope that the movements, the music, the emotions I find so much joy in cannot be a way of justifying supremacist views of culture.

Later, I came to Chennai to join one of the most prolific institutions for Bharatanatyam in India and the world, an institution that has played an important role in shaping the current state of the dance. I was looking for a way out of Kolkata where I couldn’t find a sky for my dance—neither in my dance classes nor in the progressive ivory tower called university. I joined this institution because that was the easiest thing to do in this completely unfamiliar city. But it meant that I had to confront the revisionist history of Bharatanatyam and its implications for the present.

As the nationalist movement grew in the first half of the 20th century, the demands for a “healthy” and “respectable” state became stronger. This entailed moral condemnation of the hereditary dancers from various political camps. The lifestyles of women performers from courtesan castes across South India were morally condemned and criminalised. At the same time, the search for a national dance heritage led upper-caste cultural activists to this dance form polished by the hereditary practitioners. Taking cue from the Orientalists, the upper-caste activists promoted a narrative where the dance was retrofitted right to Bharata’s Natyashastra and the hereditary castes were blamed for the art’s “degeneration”! Oppressor-caste men and women positioned themselves as “saviours” and “reformers” while hereditary dancers were shamed. Despite protests and demand voiced by hereditary dancers’ associations, The Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act was passed in 1947, shortly after Independence, criminalising the dancers’ livelihood. Even as the women of the communities remain disenfranchised to this day, casteist, state-supported institutions continue to promote the fabricated past of the dance and Brahminic ideology in all corners of the world. The overarching reach of these Brahminic institutions does not let the few dissenting voices make it to the thousands of students learning the dance.

It took me more than a decade and a half of dancing to learn the history of the dance and start to figure out the devious choreographic patterns, but before that came four years of un-dancing.

I spent my time at this institute of national importance in Chennai trying to prove that I’m a dancer. I bent and touched the floor. I twisted my upper body in painful contortions. I moved with breath stuck in my chest to arrest even the slightest movements of the hip. I jumped when they asked me to, with all the heaviness of put-on ease. I forgot my dance to dance the way they wanted. In the process, I lost my dance and could never do theirs. How could I, when the way I reacted to rhythm, music, emotions, and my surroundings was entirely different? But that’s wrong, isn’t it? Those are just excuses made by the incapable, aren’t they? Yes, I’m an incapable dancer—my limbs don’t create the perfect lines, I don’t smile right, my facial expressions are not photogenic—I’m too much. With the shame of being a counterfeit dancer, I clung to my thinness. I saw large numbers of students being forced to discontinue after spending years’ worth of sweat, pain, humiliation, and college and hostel fees—just because their body type didn’t fit in the institutional aesthetic straitjacket. I believed my incapability was tolerated each semester with passing marks, just because I looked thin.

Beauty and aesthetics can be dangerous motivations. Hegemonic powers go unchecked in the name of beauty. Intellectual disagreement with an ideology falls short of the deep need to feel desired. It makes you perpetuate the same gaze you’re fighting. The will to put oneself through pain for fitting in, combined with the glorification of ‘submission’ in the Indian ‘classical’ arts, enables a lot of violence. It also makes the dance class an ideal ground for promoting casteist, xenophobic ideas to already vulnerable minds.

The dance form of Bharatanatyam, as we see it today, was largely developed in various royal courts of South India around the late 18th and early 19th centuries. These multilingual courts were places where many cultural strands were woven together to form a dance style meant to entertain members of the courts. Erotic poetry in various languages, Islamic aesthetic influences, English band music, indigenous dance and musical traditions—all of these and more came together in Bharatanatyam.

Historically, the dance was practised and developed by temple and court dancers and dance teachers of mostly Tamil- and Telugu-speaking regions in the southern part of India. While women of these communities, from Shudra caste locations, used to dance and sing, men were traditionally employed as dance teachers and conductors for concerts. In a quasi-matrilineal community, the dancers were not bound by a caste-endogamous marriage system. They chose their partners, upper-caste and upper-class men who were also patrons, enabling the dancers to continue their art practice and sustain themselves. This was a caste-dictated practice that didn’t render these women equal to or as autonomous as their patrons in any way. Though they were marginalised and fetishised, they were still not robbed of their livelihood and art.

Of course, this is not the history one learns in today’s dance institutions. The mythology that’s taught in the name of history in our classes hails the founder of the institute, Rukmini Arundale, as one of the “saviours” of the dance. They tell students how in the early 20th century, Arundale “cleaned” the dance, got rid of the “unnecessary” and “immoral” aspects and made it suitable for dancers and audiences from “respectable” families. We listen as they tell us that she, a Brahmin woman, after learning the dance for barely a few years from a great hereditary artist, Mylapore Gowri Amma, and another legendary teacher from the hereditary community, Pandanallur Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, went on to “revive” Indian dance. She’s hailed for making the dance “spiritual” which is supposedly how the dance was “originally”. Today’s dance history even erases the role of the hereditary dancers and teachers who taught in these very institutions during the early years. While participation of Brahmin musicians such as Mysore Vasudevacharya, Tiger Varadachariar and others in the creation of the institution’s performance repertory is well documented, the presence of Karaikal Saradambal, Chokkalingam Pillai, Kattumannarkoil Muthukumara Pillai and Karaikal Dandayudhapani Pillai in the formative years of the institution is barely noted. Not only did they teach privileged-caste students, but it is evident from S. Sarada’s book, Kalakshetra-Rukmini Devi: Reminiscences, that they also had an important role in choreographing and imparting quite a few compositions that are taught to current students as Rukmini Arundale’s choreography. Even outside the institution, the dance underwent thematic and modal transformations to cater to the changing demands of the audience under hereditary masters such as Vazhuvoor B. Ramaiah Pillai. Patriotic and religious songs came to be the new favourites and film became the most popular medium. Ramaiah Pillai is known for his choreographies for early Tamil films such as Maya Machindra (1939), Dakshayagnam (1938), Ashok Kumar (1941) and so on. While the 1947 Act effectively stopped women from the hereditary castes from performing, the men continued to teach privileged-caste women who increasingly populated the stage. Many popular dancers post-1947 were essentially taught by hereditary teachers. Besides Ramaiah Pillai, other sought-after teachers included his son Vazhuvoor Samraj, Karaikal Dandayudhapani Pillai, S.K. Rajarathnam Pillai and others. This exposes the lie taught in dance institutions in the name of dance history that relegates hereditary communities to a mythical past and erases them from the contemporary.

History syllabi tell us how Bharata thought of this dance at the behest of the gods; in the theory hours we utter slokas listing physical features that make one an ideal dancer, and in the practical classes we strive for angashuddhi (purification of limbs or movements). Straight and straight lines, no deflections, no excess, no flux—everything has to be measured and in proper place, the sari pleats, the strand of hair, the crook of the elbow, the flick of the wrist, the stretch of the calf, the tightness of lips, the size of a smile, the directness of glance, the sadness, the anger—measure and quantify. Don’t be too much—it’s not respectable, it’s not aesthetic, it’s not spiritual.

Spiritual is acceptance of all they say and dancing the way they want. Many choreographies taught to students that you can trace back to hereditary dancers have been edited because the ‘reformers’ didn’t deem the content of the song moral, they crossed the line of “respectability”.

Teaching those rewritten, morphed, truncated choreographies to students, through a language of revivalist nostalgia for a past that never existed, is nothing but a projection of the desire for a Brahminic, patriarchal nation as spiritual. But where this ‘spirituality’ exerts its stranglehold most efficiently is in our mind and gaze.

The propagation of seemingly innocent ideas of beauty gilded with Brahminic notions of purity, patriarchal morality, gender roles and merit makes sure that those who fit in don’t question the system, and those who don’t, blame themselves for it and imbibe the gaze.

Every week, for an hour, we had to sit through a Bhagavad Gita lecture. This was just one of the many “spiritual” exercises every dance student was compelled to undergo. The lecturer, an old Brahmin man, used to read out one sloka from that book and then expound on it. During one such lecture in 2016, I was jerked out of my daydreaming by his criticism of the young generation marrying according to their will and how he sympathised with their parents’ hostility. Barely one month had passed since Rohith Vemula was murdered by discrimination and every single day, there was news of caste murders in various states—and here we were, learning about Indian traditions and spirituality in the idyllic atmosphere of this campus.

Sadly, this is not the story of just one college. Wherever you turn—be it a conservative space or a progressive one—you cannot escape reiterations of this casteist telling of cultural history and the violent aesthetic demand to fall in line. Where will one run to?

It’s easy to criticise the conservative spaces and consider oneself superior. But when you realise the pervasiveness of the problem, that not only the history taught to us is a lie but the true history is also painfully violent and continues to be so by our complicity, one needs to sit with it.

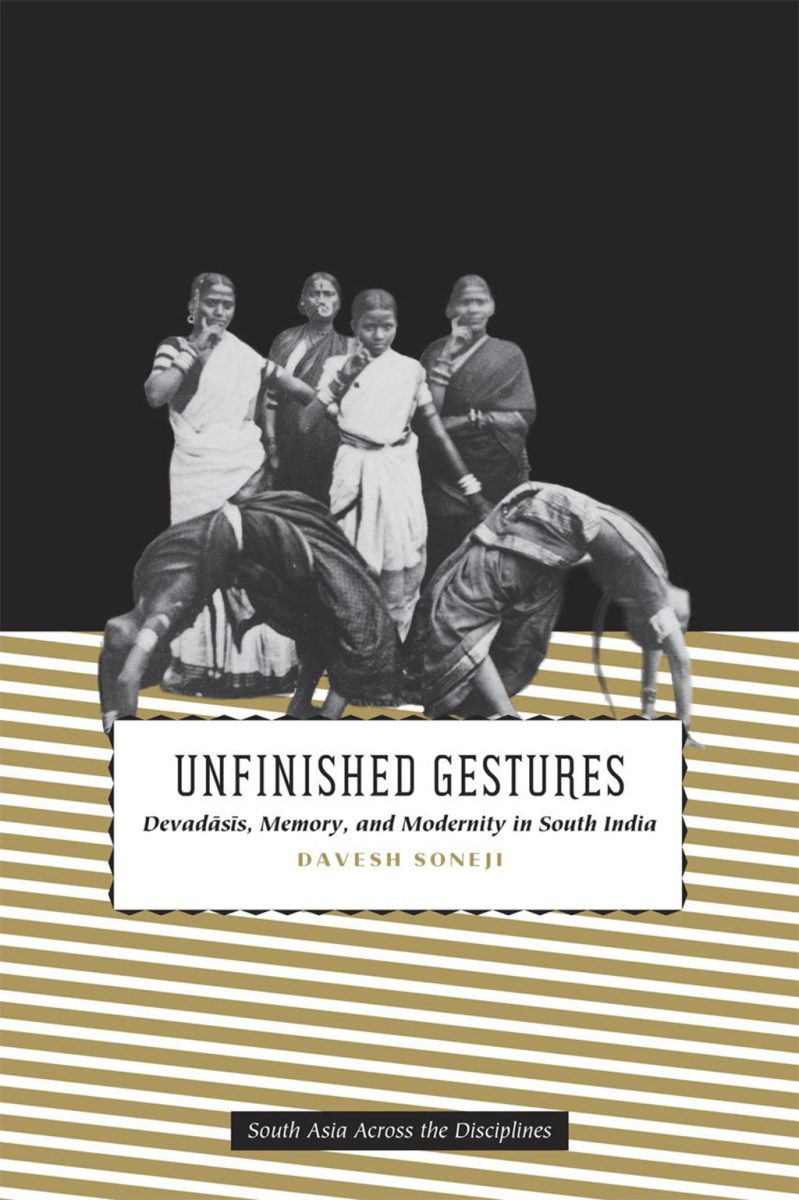

I remember coming across historian Davesh Soneji’s essay on Kalavanthulu dancers, the hereditary dancers from Andhra Pradesh, on the dusty bookshelves in the college library. This was the first time I got an inkling of the casteist project that is Indian ‘classical’ dance. It is not a case of something gone wrong, but it was wrong from its very inception.

From that epiphany to reach here has taken me more than a year. Maybe more. The painstaking work that Nrithya Pillai, a young dancer from the hereditary community, has been doing by talking about the violent history of the dance and how caste continues to suffocate difference and dissension, has been the primary inspiration in this process. As I started attending classes with her, I now encountered difficulties in remembering how to dance. As I listened to her singing, I struggled to let my body enjoy it. My limbs were now too scared to break the line even if they itched to do so. But from the first day, I knew that this was a safe space. Here, I could talk about what my body went through. Here, I wasn’t made to feel like I’m imagining injustices. I finally found a place where I could be secure in knowing that I’m not being too much. Talking, laughing, and despairing together slowly led my body to not second-guess its actions. Discussion of the history of the dance pieces—the mesh created by sociocultural upheavals through decades and how these changes make their imprints on the lyrics, the tempo, the gestures, and the tilt of the head—is no small part of our class. We recognise patterns of erasures, discuss politics of aesthetics, go shopping, discuss outfits, talk about love and betrayal, and eat out—a lot.

Even when I’d manage to break free and feel happy with my dance, a look at its video recordings would fill me with shame for my ineptness. I’m still not free from the gaze, I don’t find my body beautiful when it moves in the way it wants to. But the happiness of moving the way I want is much bigger than the shame. I choose to prioritise that joy over codes of beauty and propriety. Maybe, one day, I will overcome the internalised shame and won’t cringe at my happiness anymore.

A Short Reading List:

Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory and Modernity in South India by Davesh Soneji

Re-Casteing the Narrative of Bharatanatyam by Nrithya Pillai

Living History, Performing Memory: Devadāsī Women in Telugu-Speaking South India by Davesh Soneji

Bharatanatyam: The Choreography of a Brahmanical Past by Rituparna Pal

Hindutva’s nation-building project and how ‘classical’ dance has contributed to it by Rituparna Pal

Cycles of cultural violence within performance and scholarship of Bharatanatyam by Nrithya Pillai

Kalakshetra abuse controversy should force a rethink of power hierarchies in ‘classical’ dance world by Nrithya Pillai